How I Helped My Partner Learn to Code

When my partner Siobhán decided she wanted to make a career change into data science last spring, I knew it would be a chance for me to see first-hand how someone learns to code today.

I’ve been programming since I was a kid, and in my role as a developer and engineering manager I’ve always worked with people who have been coding for at least a year. But to start at the beginning? Where is the beginning, anyway?

For Siobhán, the starting point was the data analyst Nanodegree at Udacity, which she began last summer and completed in February. This program demands that you have taken an intro CS course, but when she started it last summer she hadn’t done any programming before. So, at first my role as her coach was to provide material from other sources (like the excellent CS50 course from Harvard) to complement what she was learning from Udacity.

She had a lot of questions, from the practicals of using the text editor and the command line, to conceptual questions that challenged her model of how computers work. A good one she asked early on was, “Why do I need to use Chrome to access Jupyter, when it’s already on my computer? Isn’t Chrome only for connecting to web sites?” Which led to a great discussion of client/server architecture, TCP/IP, HTTP, and the localhost loopback network.

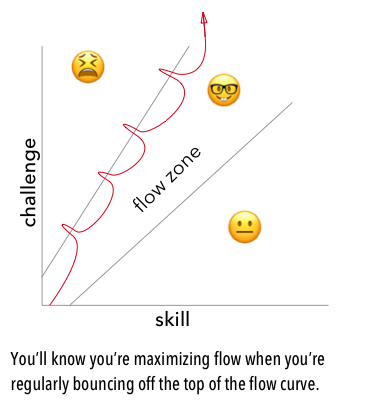

Siobhán works super hard, getting up at 6am most days and studying until late. One of the big challenges is to help her stay in the flow zone without getting overwhelmed by the amount of material she is learning. Here’s how we’ve approached this:

Getting overwhelmed every once in a while seems like the only way we can ensure that she is maximizing flow. But obviously we don’t want to stay there for long. That anxiety state, when you have something way too challenging on your hands, is very uncomfortable and it can be a drain on your overall confidence and excitement. So, whenever we hit that point, we back up and reassess.

At one point last fall, she made a list of what was being covered by the Udacity program, and it looked something like:

-

Python / Jupyter

-

R / R Studio

-

vim

-

git / GitHub

-

the command line

-

statistics

-

machine learning

-

matplotlib / pandas / NumPy / SciPi

-

JavaScript / D3

-

core CS principles & algorithms

-

data cleaning / JSON / XML / etc.

-

SQL / PostgreSQL

-

NoSQL / MongoDB

Udacity’s program was a great survey course of all of these worlds, but it covered a lot of material and there was a dizzying context switch each time Siobhán would finish a project. For example, after a few weeks learning JavaScript and D3 and building a visualization, and she’d have to move on to the very different world of R and RStudio, leaving JavaScript and all of its syntax completely behind.

In the Udacity program, she built a dozen or so class projects and learned a ton. But when she finished the program in February, her confidence plummeted. There were moments when she felt she’d learned nothing because she had had such a fleeting experience with each language or set of tools.

So she decided to do a few weeks of simple practice. The goal of the practice period is to get used to delivering complete projects using only Python, SQL, and data analysis libraries, while continuing to build core CS and statistics knowledge. With each week of this, her confidence has improved dramatically. She has seen just how much she already knows, and she’s able to focus on where she wants to fill in her understanding and fluency. By returning to the desk every day to work on Python full-time, she is quickly becoming a pro.

We’re wrapping up the practice period in mid-April, just as her job hunt is ramping up. Here’s a few things I’ve learned so far as her coach:

Express an algorithm as an idea

An algorithm may be most easily expressed as an idea. If you’re having trouble solving a coding challenge, talk through it in your native language first, not in pseudocode. There are usually several ways to pseudocode a solution (iterative, recursive, OO, functional, procedural), but there are far fewer core approaches for developing a solution.

Let’s imagine you’re trying to find the longest palindromic substring of a given string. So, for example, if the string is aabbdcaacd, the longest palindromic substring is dcaacd.

Here’s how we might approach the problem, in English:

-

Let’s try to find palindromes! Because they are symmetrical, we can start by looking for the centers, or “seeds” of palindromes within a string.

-

When we find a seed, we can try to expand it outward until the left and right sides are not equal anymore.

-

A little playing around will reveal that there are two- and three-character seeds. For example, both

aaandabaare seeds. -

Palindromes might overlap. If the string is

rrgrrgra, we don’t want to ignorergrrgrjust because we happened to find the overlappingrrgrrat the beginning of our search.

Once you have stated the plain-language idea about what you’re going to do, getting to pseudocode (and the solution) becomes a lot easier. This process also gives you better language that you can use when you start naming things in your program.

Learn to look at code

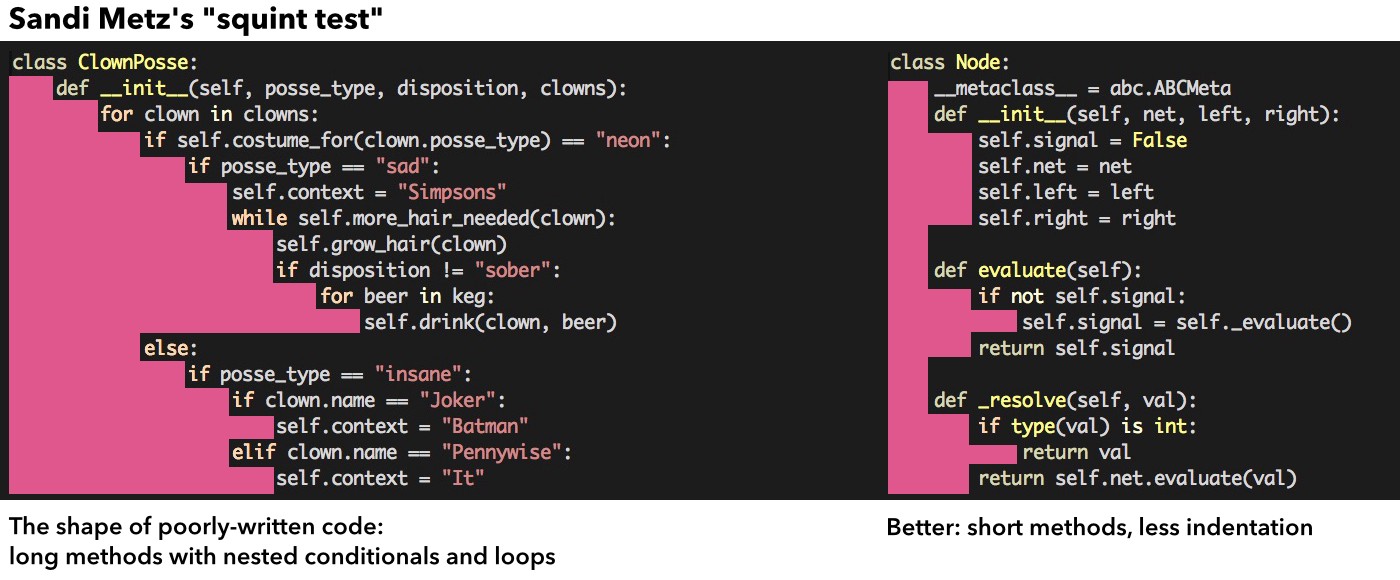

Learning to code isn’t just about writing code, it’s about learning how to scan a program for overall structure, functionality, and for red flags. It’s not so much reading, like we do in English. It’s looking.

At first, you’re simply trying to be able to make sense of all of the syntax as you build a model of the program in your head. Once the syntax becomes easier to look at, you’ll start noticing syntax errors sooner. Eventually something will just look “off” about the code when you look at it. Missing parentheses or quotation marks will stand out visually. (How your text editor treats syntax highlighting becomes meaningful at this stage.)

Object-oriented design guru Sandi Metz talks about the “squint test” she sometimes uses to look at code: squint at the code, looking at the shape of indentation and the color. If the shape looks like a jagged set of stairs or if the colors are a patchwork, it might be a good candidate for a refactor.

Start by mastering the 50 line program…

I think there is an initial plateau that you should reach for when learning to code: The 50-line procedural program. During this time, when you are learning the building blocks of data types, loops, and conditionals, it makes sense to keep your programs short.

If you become a master of these small programs, you will have an excellent foundation to build upon. The solution to any coding challenge on Leetcode or Cracking the Coding Interview can be written as a small program, so these are great practice.

And in a small program of 20–50 lines, it may be totally fine to use several global variables or to not write tests. But eventually you’re going to want to reach for the second plateau…

…then learn to keep larger programs simple

Once you have nailed simple procedural programming, you can theoretically write any program. You may even begin to believe that programming is easy.

But as your programs grow, the standards go up. You will need to develop more ways to manage complexity, and there is a second steep hill to climb. You want to keep your programs simple, so you learn the subtleties of abstraction and encapsulation that keep code simple. You learn to think more seriously about testing and about how you name things.

You will know you’re on your way to the second plateau when your initial cockiness about reaching the first plateau is replaced by the humble awareness that while programming is simple, it is not always easy.

“Simplicity is a prerequisite for reliability.” — Edsger W. Dijkstra

Get into the habit of writing tests

Writing good tests is its own skill, but it’s easy to get started. Test-driven development will help you build the discipline of good testing, because it encourages very high test coverage. And it’s addictive.

One approach is to start writing tests and code to cover the obvious base cases, then try to break the program by providing edge cases. To reach an edge case, change one of your program or function’s parameters to an extreme value. Sometimes, an “extreme value” is simply a boundary value like 0 or 1 or an empty string. Test around that value to be sure your program is doing the right thing in each case.

Sometimes the answer with extreme inputs to a function is to for an exception to be raised, and often that doesn’t involve writing any additional lines of code.

Take notes as you work

Every developer should have a little notepad next to them (physically or virtually) for notes and questions. When you’re working, a lot of things will come up that you may not want to deal with right away. Here are some notes from yesterday:

-

Python code always gets screwed up when I paste it into vim! Ugh.

-

Why do we always write

if __name__ == '__main__':? What does that mean? -

Why does my unittest suite always have to be defined as a class?

When in doubt, just write it down and see if it is something you want to follow up on later.

The most important thing Siobhán is doing right now is coding every day. We still have a few weeks to go before she is in full-time job hunt mode, but the practice will be an ongoing thing. Every day she is reinforcing concepts and building her understanding. It’s gratifying to watch, and it has helped me rekindle my excitement about just how much fun programming can be.