“The Art of Computer Programming” by Donald Knuth

Some books look so beautiful on the shelf. Not only for their aesthetic virtues, but for what their spines say about the owner. The four hardbound volumes of Donald Knuth’s “The Art of Computer Programming” — all snug in their dark purple case — send a clear message: Step aside, Muggles, because you’re in the presence of a Real Programmer. A Serious Practitioner of Computer Science.

Bill Gates once said, “If you think you’re a really good programmer… read Art of Computer Programming… You should definitely send me a résumé if you can read the whole thing.”

For me, the act of ordering this series felt like a major professional accomplishment. I allocated a special place on my shelf for these books before they arrived, as one might make room out in the barn for a shiny new mainframe.

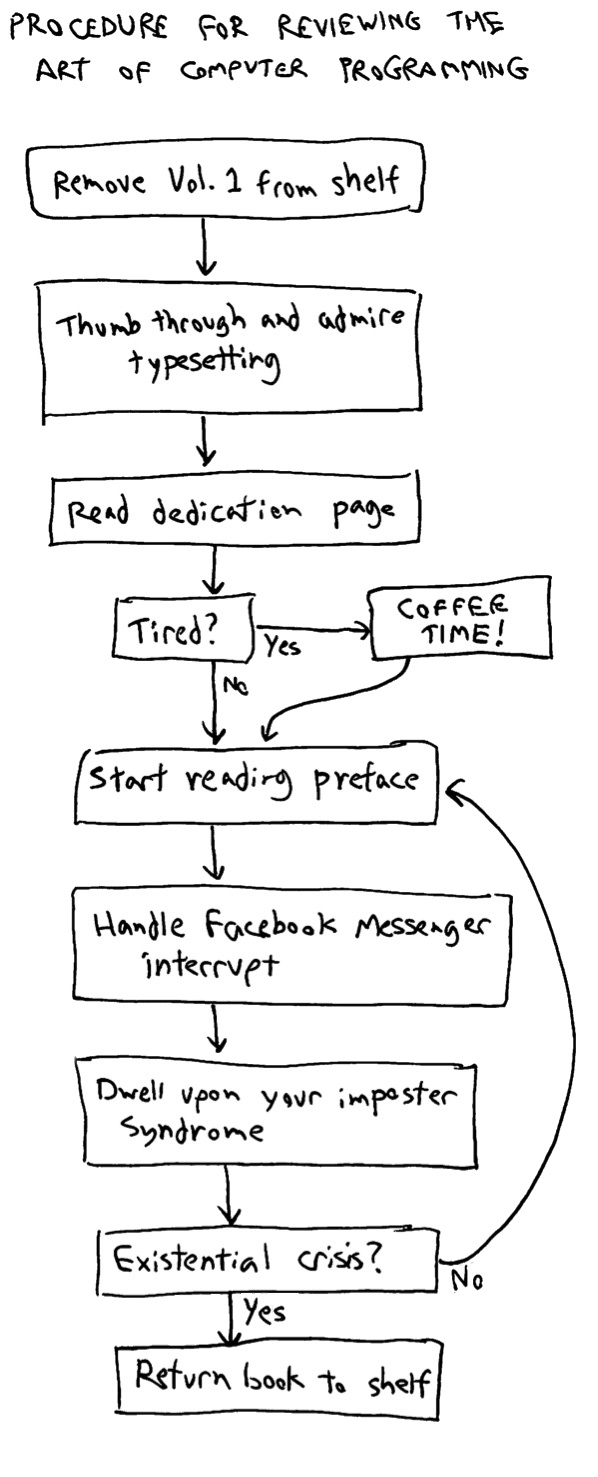

The weight of their authority was so great that they became immovable. So I never read them, and this isn’t really a book review of the series. Sorry not sorry.

This also isn’t one of those reviews where the reviewer walked out of the movie early, in disgust. Knuth’s books are epic, and he is truly a master of the fundamentals of computer programming, its origins in mathematics, and the intersection of the two fields. So much respect.

It’s just that I’m not worthy of the depths of TAOCP.

I’ve read the preface of Volume 1 three or four times, and I’ve tried to imagine how it would feel to complete the entire series. I would disconnect from the Internet for a few months and move alone to a cabin on a Wyoming mountaintop with a ream of paper, a couple boxes of pencils, TAOCP, a few supplementary math books, and a 90 day supply of Adderall.

I would take long hikes in the mountains, thinking deeply about the fundamental algorithms. No laptop, no wifi, no electricity — these are all distractions. After sunset I’d read and work problem sets by candlelight, and my dreams would be joyrides through a universe of harmonic numbers, binomial coefficients, and nonlinear data structures.

But that’s never going to happen. So, yesterday as I was reviewing the preface again, I felt I should pause and reflect on my journey so far.

Such is Knuth’s love of computers, that the entire series is dedicated to one: the IBM 650 mainframe that was popular in the 1950s. It was the first “mass-produced” computer and it cost a few hundred thousand in todays dollars. This is the machine Knuth cut his teeth on.

To be excited about computers in the 1950s was to be excited about applied math. The early IBM 650 had basic math operations and control structures, and it was built around decimal math, not binary.

There was no display and no command line. The human was the operating system: a control console allowed The Operator to start and stop programs and so on.

Say you wanted to write a program to generate fibonacci numbers. FORTRAN didn’t exist yet — that came four years after the 650 was released. So, in those early years you had to write out the machine-level operation codes for what you wanted to do, and then hand-assemble your program and punch out a deck of cards with your program stamped into them using a key punch machine.

There were a couple ways to optimize your program. You could design a faster algorithm or deploy data structures that are better suited to the problem.

You could also optimize how your program loads and runs — working with the grain of the machinery. Magnetic drum memory, a forerunner to the modern hard drive, was the primary memory for the 650, and it was very slow. So your goal as a programmer was to minimize the rotational latency of the 12,500 RPM drum machine such that all of your code and data would be easily within reach of the CPU at the right moment during execution. You wanted perfect synchronization between the CPU cycles of the mainframe and these drum memory rotations.

Computer programming was forged here, at the rough intersection of mathematics and mechanical engineering. It could be completely understood by one very smart person. That is no longer true. Knuth and the programmers of that era had to be smarter than the IBM 650. They understood every vacuum tube and control switch. We are no longer smarter than our computers in this way.

In the first paragraph of the preface, Knuth calls programming “an aesthetic experience much like composing poetry or painting.” I think this aesthetic beauty still captivates every aspiring programmer. After traveling a great distance along an exponential curve since the 1950s, it’s comforting to know that beauty remains intact. Though we no longer hammer out software and feed it into a hot, loud calculator, the beauty of programming still infuses every layer of abstraction.

I wonder how the performative nature of writing software was shaped by the constraints of hand assembly within 8kb of memory, and by the labor of crafting punch cards. I imagine writing code in Knuth’s time had the thrill and the risk of walking a high wire. Small mistakes were painful.

Since then, decades of abstraction have stacked up like a pile of mattresses, and most of us just roll around on top.

The short feedback loop and malleability of today’s software comes with a price. While software development can be much more playful today, it’s also easier to hack before we think, and it can create a lot of problems. Great software still does require a lot of thought, and with ease we lose rigor.

The IBM 650’s constraints were hard and fast, and today’s constraints are softer and often self-imposed. The tiny screens of mobile phones have heralded a wave of innovations in economical software and interface design. And it strikes me that whoever chooses the constraints of the target development environment is choosing the playing field for our future innovations.